The Neurological and Psychological Effects of Fibromyalgia in Women

Fibromyalgia Syndrome is a disease that may affect women’s psychological and neurological wellbeing. Fibromyalgia Syndrome (FMS) is defined as a musculoskeletal pain and tenderness throughout the body (Bjorkegren, Wallander, Johansson & Svardsudd, 2009). FMS is a chronic illness. I hypothesized that FMS may negatively affect women both neurologically and psychologically. The purpose of this paper was to illuminate this illness by discussing the causes of Fibromyalgia, diagnosis process, neurological effects, psychological effects, relationship issues that one faces when diagnosed and the treatments available to help ease these effects in FMS patients.

Fibromyalgia Syndrome is a disease that may affect women’s psychological and neurological wellbeing. Fibromyalgia Syndrome (FMS) is defined as a musculoskeletal pain and tenderness throughout the body (Bjorkegren, Wallander, Johansson & Svardsudd, 2009). FMS is a chronic illness. I hypothesized that FMS may negatively affect women both neurologically and psychologically. The purpose of this paper was to illuminate this illness by discussing the causes of Fibromyalgia, diagnosis process, neurological effects, psychological effects, relationship issues that one faces when diagnosed and the treatments available to help ease these effects in FMS patients.

The Neurological and Psychological Effects of Fibromyalgia in Women

Frequently, many women in today’s society deal with chronic illness. Chronic widespread pain is the symptom of many illnesses, but particularly these symptoms are seen in Fibromyalgia (Mundal, Grawe, Bjorngaard, Linakar, & Fors, 2014). The purpose of this paper was to evaluate the research of the neurological and psychological wellbeing of female FMS patients. In doing so, the aim of my research was to explore this disease and determine the causes, how it is diagnosed, the neurological and psychological effects, the difficulties of relationships when dealing with Fibromyalgia, and how this disease is treated to maintain a healthy and satisfying lifestyle. Fibromyalgia may negatively affect the neurological and psychological well being of women who have been diagnosed with this chronic pain.

Fibromyalgia is a steadily growing subject in the medical field. It has become a highly diagnosed and misdiagnosed illness throughout the world (Topbas et al., 2005). This debilitating disease is important to understand because women are affected both neurologically and psychologically (Desmeules et al., 2012; Montoro, Duschek, Muñoz Ladrón de Guevara, Fernández-Serrano & Reyes del Paso, 2014). Fibromyalgia affects the anatomy of the brain, muscles, and nerves throughout the body that causes fatigue, sensitivity, and severe pain (Bongiorno, 2012).

This disease also affects one’s psychological well being. Many experience depression and anxiety (Desmeules et al., 2012). The more one can understand about this disease, the more one can treat and live with fibromyalgia. In approaching this subject, the following areas of psychology will be addressed: neurological psychology, social psychology and health psychology. By using neuropsychology, the reader should be able to better understand and explain how fibromyalgia can affect the brain and physical elements. Social psychology will be used to address how this disease affects people’s feelings and behaviors. Health psychology will address the psychological and behavioral factors in which contribute to this disease.

According to Tobas et al. (2005), the prevalence of fibromyalgia in the female population was approximately 3.6% for 20-49 year olds while this percentage ranged higher at 10.1% for 50-59 years of age. With the frequency of occurrence becoming more prominent, it is important to understand this disease including the symptoms and causes. Fibromyalgia is a clinical disease that is often concluded to be only “of the mind” (Wait, 2014). Though this disease is now considered a clinical, neurological disease and often includes a long journey to a diagnosis.

Diagnosing Fibromyalgia

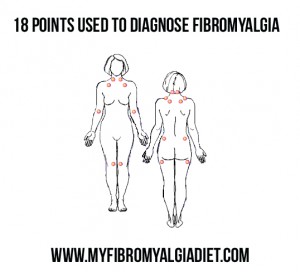

Unlike many diseases, Fibromyalgia is not usually the first diagnosis and comes after many different tests for other autoimmune diseases such as lupus. According to Wierwillie (2011), the general case would be a woman who has suffered from chronic pain for a time period greater than three months. The pain is usually widespread in the muscles and joints throughout the upper and lower body (Wierwillie, 2011). In addition to the widespread pain, many patients also experience stiffness and severe fatigue. This musculoskeletal disease falls within the category of muscular rheumatism which defines symptoms that gradually onset in different locations of the body and eventually radiate across the entire body (Wierwillie, 2011). The physician, after many times misdiagnosing due to similar symptoms of other diseases, perform a physical examination that reveals an enhanced pain in at least ten points in specific locations on the patient’s body (Wierwillie, 2011) (see Appendix A for tender point chart).

Fibromyalgia is too often misdiagnosed because symptoms and severity does not always align with the diagnostic criteria (Wierwillie, 2011). Per Wierwillie (2011), the diagnostic criteria cannot be applied universally, which causes an “absence of absolute”. There is not a blood test or scan that can positively identify or diagnose one with fibromyalgia (Wierwillie, 2011). Dealing with doctors throughout the process of diagnosing this disease is not always easy. Often doctors and the misdiagnosis of Fibromyalgia can be hard on the patient and not always helpful to the patient (Undeland & Malterud, 2007). Fibromyalgia patients experience disrespect, misunderstanding, and limitation to the care they receive from their doctors because this illness is invisible to even the trained eye (Undeland & Malterud, 2007). Fibromyalgia encompasses many neurological and psychological effects that the right doctor can examine and diagnose.

Neurological Effects of Fibromyalgia

Implicit memory function is affected in fibromyalgia patients (Duschek, Werner, Winkelmann, & Wankner, 2013). It refers to the unconscious awareness of the influence of past experiences on current behaviors in current experiences (Duschek, Werner, Winkelmann, & Wankner, 2013). The researchers found that in fibromyalgia patients showed significantly fewer correct answers when given an implicit memory task. The healthy controls scored significantly better. These results were translated into suggestions that imply there was impaired implicit memory function that reduced the influence of the patient’s behavior (Duschek, Werner, Winkelmann, & Wankner, 2013).

Fibromyalgia patients may experience many different neurological effects. Per Montoro, Duscheck, Guevara, Fernandez-Serrano and Reyes del Paso (2014), there is evidence that suggest that fibromyalgia patients suffer from cognitive deficits. One way of investigating this idea is to measure the aberrant cerebral blood flow response during a cognition task. Cerebral blood flow is important because it has been researched and evidence points to a relationship between it and neuronal activity (Guevara et al., 2014). Neuronal activity is an important factor in why people with fibromyalgia may experience brain “fog” or lower brain activity versus the brain activity or cerebral blood flow of a healthy woman (Guevara et al., 2014). Cerebral blood flow and cognitive abnormalities are one of many neurological effects.

In related functioning, SNAP-25 protein was shown to contribute to synaptic vesicle fusion and the plasma membrane in neurotransmission throughout the brain (Balkarli, Sengul, Tepeli, Balkarli & Cobankara, 2014). The SNAP-25 protein may be a key indicator of neurological effects of brain in fibromyalgia patients (Balkarli et al., 2014). An increase in the SNAP-25 gene has been seen in patients with fibromyalgia. This gene has been seen as a factor in other diseases and disorders and could be one of the main reasons for the neurological, psychological and cognitive disorders seen in fibromyalgia patients (Balkarli et al., 2014).

Other symptoms related to fibromyalgia are tension headaches, irritable intestine syndrome, and myofacial pain syndrome that fall in the central sensitization syndromes (Balkarli et al., 2014). The musculoskeletal pain and tenderness fall within the etiopathogenesis category (Balkarli et al., 2014). The relationship between the SNAP-25 protein and etiopathogenesis have been studied but not clearly known. The researchers documented through studies that there was an increase in SNAP-25 protein in fibromyalgia patients versus healthy women (Balkarli et al., 2014). It could be that these factors may be a way to genetically test for fibromyalgia. This was not the only link that exists between neurological pathways and fibromyalgia.

Fibromyalgia has also been linked to the prolonged immune-hormonal pathways (Breeding, Russell & Nicolson, 2012). The immune activation is prolonged periods, which affects the oxidative and nitrogenous stress, which leads to hormonal subjugation, fatigue, and neuropathic pain (Breeding, Russell & Nicolson, 2012). These pathways may serve as the reason to the chronic nerve pain that fibromyalgia patients experience on a daily basis (Breeding, Russell & Nicolson, 2012). These pathways could also be a cause or trigger of fibromyalgia. Issues such as traumatic event, emotional stress or unresolved chronic infection may be a partial explanation for the onset of fibromyalgia syndrome (Breeding, Russell & Nicolson, 2012).

A dysfunctional central pain processing mechanism leads to a generalized pain sensitivity that explains the widespread chronic pain associated with fibromyalgia (Stahl, 2009). There are pathways that run through the spinal cord that are involved in the perception of pain through the higher brain centers (Stahl, 2009). These pathways consist of several neurotransmitters that affect pain, mood and many other symptoms that are seen in fibromyalgia patients. The neurotransmitters involved are serotonin, noradrenaline, and others such as dopamine (Stahl, 2009). Per Stahl (2009), nociception input are ascending and descending pathways that are a part of the bidirectional process of neuronal passing through the spinal cord to the brain. These pathways act as modulators of pain perception and regulate the pain pathways. There is an abnormality in this pain processing in fibromyalgia patients. These neurotransmitters are not only involved in pain perception and processing, but these same neurotransmitters also affect the psychological well being of fibromyalgia patients (Stahl, 2009).

Psychological Effects of Fibromyalgia

Psychological distress has been reported to be elevated in patients with fibromyalgia (Sayar, Guleca, Topbas & Kalyoncu, 2004). Specifically, patients report depression and anxiety as two main effects of fibromyalgia (Sayar, Guleca, Topbas & Kalyoncu, 2004). Per Sayar, Guleca, Topbas and Kalyoncu, (2004), depression ranges from 26-80% of patients with fibromyalgia along with 51-63% of patients deal with anxiety. As one may see from these statistics, comorbid depression and anxiety does exist among fibromyalgia patients. The psychological distress may be related to the degree of pain that a fibromyalgia patient suffers with (Sayar, Guleca, Topbas & Kalyoncu, 2004). With this knowledge, it is hard to know whether fibromyalgia causes the psychological distress or whether it is caused by the psychological distress.

Fibromyalgia patients suffer from neurological pain that is linked to emotional and cognitive abnormalities (Desmeules, Piguet, Besson, Chabert, Rapiti, Rebsamen, Rossier, Curtin, Dayer, & Cedraschi, 2012). Fibromyalgia patients, who were reported unable to wean from medicinal support for this illness, reported higher psychological distress (Desmeules et al., 2012). On a global scale, fibromyalgia patients showed a psychological vulnerability that might be connected to “a modulator in the metabolism of monoaminergic neurotransmitters called Cathechol-O-Methyl-Transferase Val158MET Polymorphism” (COMT VAL158Met) (Desmeules et al., 2012). This enzyme has been associated with psychological wellbeing of fibromyalgia patients. COMT VAL158Met polymorphism was elevated in patients who were taking medication for this illness and unable to stop intake versus the patients who were able to stop intake of medication (Desmeules et al., 2012). The COMT VAL158Met enzyme may be another insight into diagnosing when one is suffering from Fibromyalgia. The psychological well being of fibromyalgia patients encompasses more than abnormalities such as depression and anxiety.

Spiritual well being can be observed as a part of psychological well being. Spiritual well being has been shown to affect the relationship between symptom patterns and uncertainty in fibromyalgia patients (Anema, Johnson, Zeller, Fogg & Zetterlund, 2009). When one considers the symptoms and challenges that are apart of fibromyalgia, one can deduct that an individual’s spiritual well being may be affected (Anema, Johnson, Zeller, Fogg & Zetterlund, 2009). A sense of uncertainty may be a source of stress for fibromyalgia patients. Uncertainty has an effect on psychosocial well being (Anema, Johnson, Zeller, Fogg & Zetterlund, 2009).

The psychosocial well being, of chronically ill patients, has been observed to be negatively influenced by the illness (Anema, Johnson, Zeller, Fogg & Zetterlund, 2009). Symptom pattern variability, fluctuations in symptoms and activities, is related to the uncertainty and spiritual well being that leads to the adaptation of the patients psychosocial well being (Anema, Johnson, Zeller, Fogg & Zetterlund, 2009). Per Anema et al. (2009), a negative correlation was found between uncertainty and spiritual well being. Spiritual well being of fibromyalgia patients was important to their overall health, but specifically in the state of psychological well being.

Relationship Effects of Fibromyalgia

Fibromyalgia does not just affect the person physically, but it also affects the relationships between fibromyalgia sufferers and those who participate in their lives (Marcus, Richards, Chambers & Bhowmick, 2012). As stated, fibromyalgia affects the physical and emotional well being of patients. This effect impairs their daily living in many ways: ability to perform daily task, ability to work, and relationships of loved ones (Marcus, Richards, Chambers & Bhowmick, 2012). Relationships among family and friends are affected when one suffers from this chronic illness. Fibromyalgia patients have reported to experience mild to moderately damaged relationships with significant others (Marcus, Richards, Chambers & Bhowmick, 2012). Per Marcus et al. (2012), many of these relationships ended due to the effects of fibromyalgia.

The impact of fibromyalgia on relationships goes beyond the spouse or significant other. Relationships between fibromyalgia sufferers and their children or intimate friends were negatively impacted for many patients (Marcus, Richards, Chambers & Bhowmick, 2012). Fibromyalgia impacts family functioning (Murray, Murray & Daniels, 2006). Per Murray, Murray and Daniels (2006), the level of stress and symptom severity was a predicting variable of family functioning. The relationships within a life are affected by the ability of performing daily activities and life in general. When one is unable to perform daily life, it takes a toll on all those associated with them. One’s ability to adapt to the stress and physical pain of fibromyalgia can determine the effect of relationships among those individuals (Murray, Murray & Daniels, 2006).

Among the effects of fibromyalgia on relationships, an important function that was affected in female sufferers is sexual function (Yilmaz, Yilmaz & Erkin, 2012). As stated by fibromyalgia patients (Marcus, Richards, Chambers & Bhowmick, 2012), damaged relationships with significant others have been observed. Normal sexual function can be defined as stages of sexual desire including the following: desire, arousal, orgasm and relaxation and feelings of pleasure such as satisfaction and fulfillment (Yilmaz, Yilmaz & Erkin, 2012). Researchers have observed a sexual dysfunction in women with fibromyalgia (Yilmaz, Yilmaz & Erkin, 2012).

Among women diagnosed with fibromyalgia, pain is experienced in daily lives. When associated with sexual function, women have reported a lower threshold of pain that may explain the sexual dysfunction in patients (Yilmaz, Yilmaz & Erkin, 2012). When pain was experienced during intercourse, desire and arousal becomes a problem for females (Yilmaz, Yilmaz & Erkin, 2012). The dysfunction experienced may be linked to depressive moods that affect the relationships and psychological well being of fibromyalgia sufferers (Yilmaz, Yilmaz & Erkin, 2012). As one may see, fibromyalgia effects are seen in every aspect of a patient’s life. There are many different treatments to help the patients overall well being.

Treatments for Fibromyalgia

There are many different treatment options that range from physical therapy, acupuncture, exercise, myofascial release- massage, virtual reality therapy and pharmacological therapies. Many patients are searching for options in treating this chronic illness. Not all treatments work on everyone. The treatments heavily depend on the patient and their willingness to overcome fibromyalgia.

Physical therapy may be beneficial in helping fibromyalgia patients in daily routine and tasks (Lofgren, Bromam & Ekholm, 2008). Fibromyalgia affects everyday life. Performing the usual routine and task can be challenging. In physical therapy, patients can possibly learn how to decrease muscle activity during daily task, which decreases pain intensity and exertion (Lofgren, Bromam & Ekholm, 2008). Rehabilitation programs have been shown affective in helping with everyday routines and task.

Acupuncture, despite popular belief, may not be an effective treatment for fibromyalgia (Itoh & Kitakoji, 2010). As per Itoh and Kitakoji (2010), acupuncture has yet to show evidence of differences in serotonin levels that help in treating depression and anxiety. The lack of effect of acupuncture in research has not shown hope as a regular treatment for fibromyalgia. Many still report using acupuncture as a treatment though the evidence of relief does not concur in alleviating pain and depressive moods (Itoh & Kitakoji, 2010).

Exercise has been observed to help a person’s overall well being even when not dealing with chronic illness. The effect of exercise was observed in fibromyalgia patients. Self-esteem, self- concept and quality of life in patients with fibromyalgia were affected (Garcia-Martinez, Paz & Marquez, 2012). Exercise may improve psychological distress and neurological functioning (Garcia-Martinez, Paz & Marquez, 2012). Health related quality of life encompasses a person’s overall well being. According to Garcia-Martinez, Paz and Marquez (2012), exercise was observed to improve muscle strength, flexibility, health status and quality of life. Exercise also confidently improved patient’s self-esteem and self-concept (Garcia-Martinez, Paz & Marquez, 2012). Exercise has been observed as very beneficial in fibromyalgia patient’s overall well being.

Myofascial release therapy, also known as massage therapy, may be beneficial in improving many of the effects of fibromyalgia such as pain, anxiety, depression, and quality of life (Castro-Sanchez et al., 2011). Massage eased pain immediately and continued to alleviate the pain over time through the release of endorphins that may help in improving the neurological and psychological health of fibromyalgia patients. According to Castro-Sanchez et al. (2012), massage-mayofascial release significantly improved many of the effects of fibromyalgia. This treatment reduced pain at tender points throughout patient’s bodies (Castro-Sanchez et al., 2012). Massage-myofascial release therapy has produced evidence that it is very beneficial as a treatment for fibromyalgia.

Virtual reality therapy has become more popular as cognitive behavioral therapy. Virtual reality therapy has helped support the patient by adapting a virtual environment for developing mindfulness skills and relaxation (Botella et al., 2013). Many may not think of virtual reality therapy as an option for treating fibromyalgia because this type of therapy is very new in treating chronic illness. With that being the case, long term benefits of significantly reduced pain, depression and coping strategies have been observed (Botella et al., 2013). Currently, this therapy is not widely used due to the lack of evidence and knowledge of its benefits in treating fibromyalgia. The research that has been conducted has shown significant hope that this could be very beneficial in the overall well being of fibromyalgia patients (Botella et al., 2013).

Pharmacology is the most widely used therapy for fibromyalgia. When dealing with pain and psychological distress, antipsychotics can be helpful in managing chronic illness (Calandre & Rico-Villademoros, 2012). A few of the more common drugs used in treating fibromyalgia are Amitriptyline, Duloxetine, Milnacipran, Pregabalin and Gabapentin (Calandre & Rico-Villademoros, 2012). Though these drugs may not improve all of the symptoms associated with fibromyalgia, one must take into account that all people react differently to different medications. Side effects are a major downfall to this therapy. Evidence shows that immediate help may be found in these medicines, but may have to be adjusted or eventually changed over time to avoid tolerance (Calandre & Rico-Villademoros, 2012).

Low dose antidepressants are some of the most effective pharmacological therapies for fibromyalgia pain (Staud, 2010). Similarly, muscle relaxants, such as cyclobenzaprine, may improve symptoms of fatigue, overall pain, and poor sleep (Staud, 2010). Serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are frequently used as part of pharmacological therapy for fibromyalgia (Staud, 2010). Tramadol is an analgesic that binds and helps inhibit the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine (Staud, 2010). Tramadol is commonly used in treating severe pain caused by fibromyalgia. With any drug, side effects may occur, but side effects that may be experienced from a drug, Tramadol is among the favorites in treatment (Staud, 2010).

Benzodiazepines, such as anxiety medicine, are commonly used in addition to pain medicine (Staud, 2010). The effectiveness of benzodiazepines has provided inconsistent results in terms of treating fibromyalgia (Staud, 2010). Local anesthetics are becoming more widely used by injecting into the tender points of patients demonstrating significant pain relief (Staud, 2010). According to Staud (2010), there are new pharmacological therapies that show promise in treating fibromyalgia. These drugs consist of Nabilone (Cesamet), Naltrexone (Nalorex), Modafinil (Provigil), Dextromethorphan, and Sodium oxybate (Xyrem) (Staud, 2010). During studies, many medicines were helpful in treating fibromyalgia. There are many avenues of treatment available for fibromyalgia and continue to grow as more research is done. Each fibromyalgia patient is different and it may take a combination of these therapies to be effective in treating the symptoms associated with this chronic illness, but there is hope of neurological and psychological well being for all sufferers.

Conclusion

Chronic illness is becoming highly diagnosed and misdiagnosed in today’s society. Chronic widespread pain is the symptom of many illnesses, but is a particularly defining a symptom in fibromyalgia (Mundal, Grawe, Bjorngaard, Linakar, & Fors, 2014). The purpose of this paper was to evaluate the research of the neurological and psychological wellbeing of FMS female patients. The thesis was that fibromyalgia negatively affects the neurological and psychological well being of women who have been diagnosed with this chronic pain. Fibromyalgia does negatively affect almost every area in the patient’s life including their neurological and psychological well being ((Desmeules et al., 2012; Montoro, Duschek, Muñoz Ladrón de Guevara, Fernández-Serrano & Reyes del Paso, 2014). Fibromyalgia affects the anatomy of the brain, nerves throughout the body, and muscles that causes fatigue, sensitivity, and severe pain (Bongiorno, 2012). Per Montoro, Duscheck, Guevara, Fernandez-Serrano and Reyes del Paso (2014), there is evidence that suggest that fibromyalgia patients suffer from cognitive deficits. Cerebral blood flow has been researched and evidence points to a relationship between it and neuronal activity (Guevara et al., 2014). Fibromyalgia patients suffer from neurological pain that is linked to emotional and cognitive abnormalities (Desmeules, Piguet, Besson, Chabert, Rapiti, Rebsamen, Rossier, Curtin, Dayer, & Cedraschi, 2012).

Psychological distress has been reported to be elevated in patients with fibromyalgia (Sayar, Guleca, Topbas & Kalyoncu, 2004). Symptom pattern variability, fluctuations in symptoms and activities, is related to the uncertainty and spiritual well being that leads to the adaptation of the patients psychosocial well being (Anema, Johnson, Zeller, Fogg & Zetterlund, 2009). Fibromyalgia does not just affect the person physically, but it also affects the relationships between fibromyalgia sufferers and those who participate in their lives (Marcus, Richards, Chambers & Bhowmick, 2012). Among the effects of fibromyalgia on relationships, an important function that was affected in female sufferers is sexual function (Yilmaz, Yilmaz & Erkin, 2012). There are effective treatments- physical therapy, acupuncture, exercise, myofascial release- massage, virtual reality therapy and pharmacological therapies- available to help fibromyalgia patients live a better quality life (Botella et al., 2013; Castro-Sanchez et al., 2011; Calandre & Rico-Villademoros, 2012; Garcia-Martinez, Paz & Marquez, 2012; Itoh & Kitakoji, 2010; Lofgren, Bromam & Ekholm, 2008; Staud, 2010).

As with any research studies, there were methodological limitations identified in many of the articles. Past researchers have expressed limitations in observing fibromyalgia patient’s overall well being due to fibromyalgia effects varying in each patient (Anema, Johnson, Zeller, Fogg, & Zetterlund, 2009; Sayar, Guleca, Topbas, & Kalyoncu, 2004). Participants do not always report accurately when filing out questionnaires and self-reports of symptoms such as pain, intensity of pain, anxiety and depression may also be a limitation to these studies (Anema, Johnson, Zeller, Fogg, & Zetterlund, 2009; Marcus, Richards, Chambers, & Bhowmick, 2012; Sayar, Guleca, Topbas, & Kalyoncu, 2004). Additionally, many participants only represented a small group of people who were proactive in seeking and participating in studies to find the best way of symptom management (Anema, Johnson, Zeller, Fogg, & Zetterlund, 2009; Marcus, Richards, Chambers, & Bhowmick, 2012; Murray, Murray, & Daniels, 2006). Researchers recruited through clinical samples rather than a true cross-section of the FMS population (Anema, Johnson, Zeller, Fogg, & Zetterlund, 2009; Sayar, Guleca, Topbas, & Kalyoncu, 2004). These methodological limitations may be addressed in future research.

Future researchers should take greater strides to more accurately increase generalization by random sampling from a larger group of the fibromyalgia target population. The researchers should use more scientific measurements that assess biological markers and changes along with self-reports to record symptoms such as pain, anxiety and depression. Also, researchers should follow up with their participants by helping them find doctors specialized in fibromyalgia and treatments. The future research should be more in depth and encompass all aspects of a female’s well being when dealing with fibromyalgia and provide a more stable example of this illness and options of treatment.

References

Anema, C., Johnson, M., Zeller, J. M., Fogg, L., & Zetterlund, J. (2009). Spiritual well being in individuals with fibromyalgia syndrome: Relationships with symptom pattern variability, uncertainty, and psychosocial adaptation. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice: An International Journal, 23(1), 8–22. doi: 10.1891/1541-6577.23.1.8

Balkarli, A., Sengul, E., Tepeli, E., Balkarli, B., & Cobankara, V. (2014). Synaptosomal-associated protein 25 (Snap-25) gene Polymorphism frequency in fibromyalgia syndrome and relationship with clinical symptoms. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 15, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-191

Bongiorno, P. (2012). Depression, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue, and pain: shared neurobiological pathways and treatment. Townsend Letter, 351, 62–68.

Botella, C., Garcia-Palacios, A., Vizcaino, Y., Herrero, R., Banos, R. M., & Belmonte, M. A. (2013). Virtual reality treatment of fibromyalgia: A pilot study. Cyberpsychology, 16(3), 215–223. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.1572

Breeding, P. C., Russell, N. C., & Nicolson, G. L. (2012). Integrative model of chronically activated immune-hormonal pathways important in the generation of fibromyalgia. British Journal of Medical Practitioners, 5(3), 21–30.

Calandre, E. P. & Rico-Villademoros, F. (2012). The role of antipsychotics in the management of fibromyalgia. CNS Drugs, 26(2), 135–153.

Castro-Sánchez, A. M., Matarán-Peñarrocha, G. A., Granero-Molina, J., Aguilera-Manrique, G., Quesada-Rubio, J. M. & Moreno-Lorenzo, C. (2011). Benefits of massage- Myofascial release therapy on pain, anxiety, quality of sleep, depression and quality of life in patients with fibromyalgia. Evidence-based Complementary & Alternative Medicine, 8, 1–9. doi: 10.1155/2011/561753

Corrales, B. S., Hoyo Lora, M., Martinez Díaz, I. C., Páez, L. C. & Ochiana, G. (2010). Health related quality of life and depression in women with fibromyalgia syndrome: Effects of a long-term exercise program. Kinesiologia Slovenica, 16, 3–9.

Desmeules, J., Piguet, V., Besson, M., Chabert, J., Rapiti, E., Rebsamen, M., Rossier, M. F., Curtin, F., Dayer, P., & Cedraschi, C. (2012). Psychological distress in fibromyalgia patients: A role for catechol-o-methyl-transferase val158Met polymorphism. Health Psychology, 31(2), 242–249. doi: 10.1037/a0025223

Downey, J. (2011). Figuring out fibromyalgia. Natural Health, 41(6), 48–55.

Duschek, S., Werner, N.S., Winkelmann, A. & Wankner, S. (2013). Implicit memory function in fibromyalgia syndrome. Behavioral Medicine, 39, 11–16. doi: 10.1080/08964289.2012.708684

Garcia-Martinez, A. M., Paz, J. A., Marquez, S. (2012). Effects of an exercise programme on self-esteem, self-concept and quality of life in women with fibromyalgia: A randomized controlled trial. Rheumatology International, 32(7), 1869–1876. doi: 10.1007/s00296-011-1892-0

Itoh, K. & Kitakoji, H. (2010). Effects of acupuncture to treat fibromyalgia: A preliminary randomized controlled trial. Chinese Medicine. 5(11). 5–11 doi: 10.1186/1749-8546-5-11

Lofgren, M., Bromana, L., & Ekholm, J. (2008). Does rehabilitation decrease shoulder muscle activity in fibromyalgia in work or housework tasks? An electromyographical study. Work, 31(2), 195–208.

Marcus, D. A., Richards, K. L., Chambers, J. F. & Bhowmick, A. (2012). Fibromyalgia: family and relationship impact. Musculoskeletal Care, 11, 125–134. doi: 10.1002/msc.1039

Miro E., Pilar Martınez, M., Sanchez, I. A., Prados, G., & Medina, A. (2011). When is pain related to emotional distress and daily functioning in fibromyalgia syndrome? The mediating roles of self-efficacy and sleep quality. British Journal of Health Psychology, 16, 799–814. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8287.2011.02016.x

Montoro, C. I., Duschek, S., Muñoz Ladrón de Guevara, C., Fernández-Serrano, M. J., & Reyes del Paso, G. A. (2014). Aberrant cerebral blood flow responses during

cognition: Implications for the understanding of cognitive deficits in fibromyalgia. Neuropsychology. 1, 1–10 doi: 10.1037/neu0000138

Mundal, I., Grawe, R. W., Bjorngaard, J. H., Linaker, O. M., & Fors, E. A. (2014). Prevalence and long-term predictors of persistent chronic widespread pain in the general population in an 11-year prospective study: the HUNT study. MC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 20(14), 213–234. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-213

Murray, T. L., Murray, C. E., & Daniels, M. H. (2006). Stress and family relationship functioning as indicators of the severity of fibromyalgia symptoms: A regression analysis. Stress and Health, 23, 3–8. doi: 10.1002/smi.1102

Sayar, K., Guleca, H., Topbas, M., & Kalyoncu, A. (2004). Affective distress and fibromyalgia. Swiss Med Weekly, 134, 248–253. Retrieved from: http://www.smw.ch/docs/pdf200x/2004/17/smw- 10421.pdf

Stahl, S. M. (2009). Fibromyalgia: Pathways and neurotransmitters. Human Psychopharmacology, 24, 11–17. doi: 10.1002/hup.1029

Stuad, R. (2010). Pharmacological treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome. Drugs, 70, 1–14.

Topbas, M., Cakurbay, H., Gulec, H., Akgol, E., Ak, I., & Can, G. (2005). The prevalence of fibromyalgia in women aged 20–64 in Turkey. Scand J Rheumatol, 34, 140–144. doi: 10.1080/03009740510026337

Undeland, M. & Malterud, K. (2007). The fibromyalgia diagnosis: Hardly helpful for the patients? Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 25(4). 250–255. doi: 10.1080/02813430701706568

Wait, M. (2014). Cracking the fibro code. Arthritis Today, 28(3), 44–47.

Wierwillie, L. (2011). Fibromyalgia: Diagnosing and managing a complex syndrome. American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 24(4), 184–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2011.00671.x

Yilmaz, H., Yilmaz, S. D., Erkin, G. (2012). The effects of fibromyalgia syndrome on female sexual function. Sex Disabil, 30, 109–113. doi: 10.1007/s11195-011-9229-1

Tender Point Chart

Thanx for posting the article! It was very good and not too technical. I, unfortunately, have had multiple med failures that actually made me much worse (some caused stomach pain, but most send me into an anxiety attack! The last one the Dr prescribed that was supposed to calm me down gave me the worst suicidal feelings I’ve ever had! NOT fun, but terrifying.) I had 2 months of TMS treatments last fall for the severe depression with little effect. A month later the Dr told me I have Emotional Intensity Disorder (formerly known as Borderline Personality.) I feel I have been rejected by so many people due to the irritability and mood swings. I can’t work much but the pain is the least of my problems. I ache all the time, but am able to ignore it unless I do too much or am sick on top of that. It’s like having the flu ALL the time.